This post is part of my ongoing series on provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act which have been under attack by conservative, and some liberal, forces. For Part 1 on the Volcker Rule, click here.

Fox News, depicting another kind of orderly liquidation of a bank.

Who Should Break Up The Banks?

As I mentioned in a blog post outside of this series, the presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders has given this topic a lot of media coverage. Some of that has been good: it has reignited public interest in bringing back the Glass-Steagall Act, and despite what opponent Hillary Clinton says, the Dodd-Frank Act’s Volcker Rule is no replacement for that act. But other parts have not been so great: after all, the Dodd-Frank Act is a complicated piece of legislation that became an even more complicated mess of regulatory rules from multiple government agencies and conflicting case law by various different district courts. The one major success the finance industry had with it was to force compromises that had even more strength in the confusion they add than the actual loopholes they create. And as I talked about in that blog post, Bernie Sanders’s campaign has stated that it wants to use the Mitigation of risks to financial stability provision, 12 U.S.C. § 5331, to break up the “too big to fail” banks in his first year. As I mentioned, that is pretty much politically impossible given the legislative requirements and just how many banks qualify as “too big to fail.”

This post is going to look at another provision: Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA) as laid out in Subchapter II, Chapter 53 of Title 12 of the U.S.C. Interestingly, Hillary Clinton in the debates has hinted that she would use this authority, specifically to go after disreputable or insolvent financial institutions. While I certainly am aware of how friendly Clinton is with the captains of finance, it is a fairly risky move on her part: OLA is largely despised by even the more liberal economists. The usual “doom and gloom” narratives (funny how they’re never about the things that actually cause recessions) have been put forth by orthodox economists of all stripes. Stephen J. Lubben, Seton Hall University School of Law corporate apologist and neo-colonialist, wrote in his piece for the New York Times “The Flaws in the New Liquidation Authority” that OLA “…is apt to destroy going concern value and result in greater market disruption…There are no easy solutions, and probably failure avoidance is a better aim than any of the proposed resolution mechanisms.” In other words, Lubben wants the market to be allowed to “self-regulate” (shocking I know). As Lubben mentions, others like the Hoover Institute want to utilize some form of bankruptcy proceeding instead of OLA. But before we delve into the alternatives, let’s look at a basic outline of what OLA is.

Previously, when a financial institution was on its way to failing, it would be handled in a fairly similar way to any company failing: through a bankruptcy proceeding. But the government, in a rare moment of clarity that only a major economic downturn can bring, realized that institutions like Lehman Brothers would not conduct themselves properly and that, rather than file for bankruptcy in a timely manner, would postpone it through accounting fraud, misinformation, and perjury. So, Congress decided to create the OLA provision of Dodd-Frank to ensure that major financial institutions would not be allowed to put themselves in the same kind of situation that Lehman Brothers was in. The process was taken out of the Bankruptcy Courts, modified to take away power from financial institutions, and handed over to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), an independent agency of the government whose whole purpose is to insure the deposits that people make at the banks they govern (I am going to stay out of the broker-dealer provisions, which are governed by the Securities Investor Protection Corporation). This change of venue is already upsetting to the finance industry: the priorities of a Bankruptcy Court have increasingly been to garner whatever capital possible for financial institutions, whereas the FDIC is looking out for the consumers (note: for many reasons, this is not the same as looking out for communities or the public, but it is an interest often in opposition with that of the major finance companies).

The FDIC’s Ten Step Programme

An orderly liquidation is a 10-step process:

- The Secretary of the Treasury, after an investigation, finds that a financial institution is at risk and contacts the FDIC and the financial institution to request that the FDIC be appointed the receiver of the institution. The institution has two options: accept, which takes it to step 4, or oppose.

- If the financial institution opposes the request, the Secretary petitions a federal district court to force the financial institution to accept the receivership of the FDIC. There is a closed, confidential hearing where the court evaluates whether or not the Secretary’s determination of the institution as at or dangerously close to default is “arbitrary or capricious.” Capricious means prone to sudden changes in mood or behavior.

- The court has 24 hours to deliberate. If it fails to make a determination, the FDIC will automatically be granted receivership. Otherwise, however the court rules, it can be appealed by either the Secretary or the financial institution to first the Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit and after the Supreme Court.

- If the financial institution accepts the initial request for receivership, the court fails to make a decision within 24 hours, or the court and any further appeals rule in favor of the Secretary , then the FDIC is granted receivership of the financial institution for three years, with two possible extensions of an additional year each.

- The FDIC as receiver now has six major responsibilities: (1) to prioritize the stability of US financial markets over the continuance of the financial institution (2) ensure that shareholders of the institution are the very last to get paid (3) ensure that unsecured creditors bear some of the losses (4) ensure that the management responsible for the condition of the institution are removed (5) ensure that members of the board of directors who contributed to the condition of the institution are removed (6) not take any equity interest in the institution.

- If you could not guess from that list, the FDIC now has near-complete control of the financial institution, and may conduct it in anyway that the normal management lawfully would.

- But unlike the normal management, the FDIC will be focused mostly on the complete liquidation of the financial institution by selling off some of its assets and transferring others to a “bridge company.”

- A “bridge company” would be an entity created by the FDIC through their receivership. It would be created in a similar manner and operate in a similar way as any corporation, with the Board of Directors being appointed by the FDIC.

- Once enough of the assets have been sold or transferred to bridge companies to avoid applicable antitrust law, the FDIC may choose to merge the rest of the institution with another financial institution upon that institution’s consent.

- However it may be partitioned out, the assets will be completely liquidated within 3 – 5 years without any costs being borne by the taxpayer. Think of it like leftovers that are about to spoil in a house of four people: you might eat some, give some to your roommates, reincorporate it into a new dish (leftover rice and beans always winds up becoming a burrito for me), and probably throw some of it away.

So What Does It All Mean?

If you think this is complicated, this is actually a major simplification of the enormity of particular limitations and additional regulations, judicial and other agency oversight of the process from beginning to end, and rules for handling outstanding lawsuits and other obligations against the financial institution.

But it does not require that comprehensive of an understanding to see that OLA actually has a fair amount of power within it. So does this makes Hillary Clinton’s preference for it more radical, or at least realistic, than Bernie Sanders’s congressional-led bank dissolution? Not necessarily. While the 24 hour default on judicial judgment is one of the strongest regulations in the sector, there are two major stumbling blocks to the process: prior to receivership, the evaluation of risk, and during receivership, the creation of bridge companies.

Risk Is The Game

As I have stated before, risk is the foundation of the finance industry. Capitalism is full of contradictions, or perhaps seventeen major ones as David Harvey divides it, and as Harvey writes one of the clever schemes of capitalism is the ability to utilize these very contradictions for the purpose of capital accumulation. A government beholden to capitalism, as ours is, will always have two interests: to mitigate risk to forestall or manipulate recession and to allow and facilitate a certain amount of risk in the markets. One of the beauties of OLA is that it provides a window for how the government views the relation between the risks of individual corporations and the systemic risk of the finance market.

This is reflected in 12 U.S.C. § 5383, which stipulates the following factors for systemic risk evaluation:

While all eyes were on the travesty that poses for democracy in Iowa, Alphabet (formerly Google) quietly posted its fourth (and first as Alphabet) quarter earnings February 1st. I say quietly because it was not put out in the media in a way that Alphabet is easily capable of, but it certainly generated buzz in

While all eyes were on the travesty that poses for democracy in Iowa, Alphabet (formerly Google) quietly posted its fourth (and first as Alphabet) quarter earnings February 1st. I say quietly because it was not put out in the media in a way that Alphabet is easily capable of, but it certainly generated buzz in

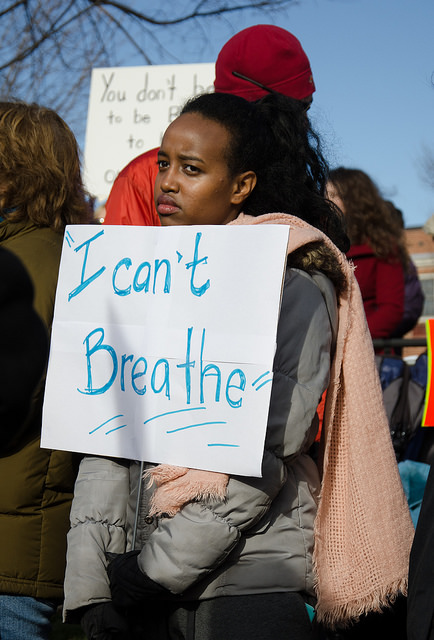

Most Leftist groups face a fairly unwieldy task of challenging a whole range of complicated issues with far less funding and time than their conservative counterparts. That is compounded by an overall focus on trying to prevent individual people from suffering which, while a noble endeavor,

Most Leftist groups face a fairly unwieldy task of challenging a whole range of complicated issues with far less funding and time than their conservative counterparts. That is compounded by an overall focus on trying to prevent individual people from suffering which, while a noble endeavor,